Read excerpts from He Wanted the Moon including the prologue below, then explore Chapter 5, written by Dr. Baird while he was being held at Westborough State Hospital, just outside Boston, in 1944.

PROLOGUE

It was the spring of 1994 when I returned from work to find the package containing my father’s manuscript on my doorstep. I was fifty-six years old and I’d been waiting for some word of him for most of my life.

It was the spring of 1994 when I returned from work to find the package containing my father’s manuscript on my doorstep. I was fifty-six years old and I’d been waiting for some word of him for most of my life.

I was a six-year-old child when he stopped coming home. My mother refused to say where he had gone, except to tell me that he was “ill” and “away.” That same year of 1944, she filed for a divorce and quickly remarried, closing the chapter of her life that included my father. I was never taken to visit him growing up; his name was rarely mentioned in our house. Since childhood, I had been informed in fleeting comments that he suffered from manic depression. I had seen him again only once, very briefly, before his death in 1959.

The late-afternoon light cast long, sharp shadows across my entranceway and the box on the step. For decades my father’s manuscript had been kept in an old briefcase in the garage of a family member in Texas, all but forgotten. I had only recently learned of its existence.

I picked up the carton and carefully brought it inside. I knew so little about my father, Perry Baird—only that he had been a doctor with a successful practice in Boston in his heyday. Yet I could vividly recall his presence in my early years: the gleaming white coat he wore at his offices, the sight of him at the Chestnut Hill train station where my mother took me to greet him, returning from his day’s work. After he disappeared, I felt the pain of a child who misses a parent, a feeling that had never completely left me.

My hands trembling slightly, I took a knife and made a slit along the packing tape on top of the carton. Opening the flaps, I peered inside, glimpsing handwriting on the top sheaf. Cautiously—as if my father’s words might bite—I took a piece of the paper between my thumb and forefinger. It was creamy and slightly translucent, of the onionskin kind used for making carbon copies in the days of the typewriter. I could see that it was covered in many lines of penciled script.

I quickly put the page back and closed the carton. After fifty years of silence, it was going to take me a little while to work up the courage to hear from him again.

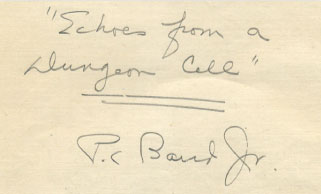

Some days later, I reopened the box, this time pulling out a handful of pages, then another. Soon, the stack on my kitchen counter was over a foot high. I attempted to read my father’s words, but it was impossible to connect the sentences on one page with the next. Further investigation revealed that the papers had been shuffled out of order. After much searching, I located what appeared to be a title written in bold strokes: “Echoes from a Dungeon Cell.”

It took many months to restore the manuscript to some semblance of order. As I rearranged the pages, I realized that these were my father’s memoirs. For the first time, I learned what had happened to him all those years ago. He had not vanished (as I had sometimes suspected as a child). He had not left us. He had been removed against his will to Westborough State Hospital, a psychiatric institution just outside Boston, where he had written about his experiences on the papers I held in my hands. My father was afflicted with a severe mental illness during a period before any effective treatment existed, many years before the advent of modern psychiatric medications. Like hundreds of thousands of mentally ill patients at that time, he was a victim of both his disease and the stigma surrounding it. He was shut away, institutionalized, his family advised to try to forget him, an edict my mother did her best to follow.

The arrival of the manuscript in my life marked the beginning of a long journey to know my father. Along with the other traces I have found of him—in letters, his published articles, his medical records, and photographs—I was able to discover not only a father, but a writer and a scientist, a man whose insights were extraordinarily advanced for his times.

Although Echoes from a Dungeon Cell was never published in my father’s lifetime, it was his great hope that it would one day find publication. In letters written after he departed Westborough, he explained:

Last year when I was ill, I went through a series of adventures both colorful and painful. At that time I was asked to write the story of some of my strange travels and so, out of the cauldron of despair, came forth my manuscript. It is a longcontinued account of every kind of suffering and disaster—February 20 to July 8, 1944. By going along slowly, depicting in detail the intricate succession of events, perhaps I can unravel and clarify the sequence of events and the relative importance of the various connecting links and contributing episodes . . .

I believe that the inadequate understanding of manicdepression as displayed by friends and relatives imposes unnecessary hardships on the manicdepressive. I have read widely about manic depression, I have lived through five prolonged suicidal depressions, four acute manic episodes and many hypomanic phases. I have learned by experience how all the treatments feel: straight-jackets, wristlets, anklets, paraldehyde injections, hot and cold packs, continuous tub, close confinement to small spaces, and all the many inventions that man has created for the manic-psychosis. As a patient, I have studied many other patients at four psychopathic hospitals, including one city and one state hospital.

Out of my recent agonies came a dauntless furor scribendi and I have written a very readable book. It is my conviction and I know you’ll agree that artistic creativeness finds its best expression after it has been fashioned by the agonies and tortures that life imposes.